Choosing Between Trade-offs

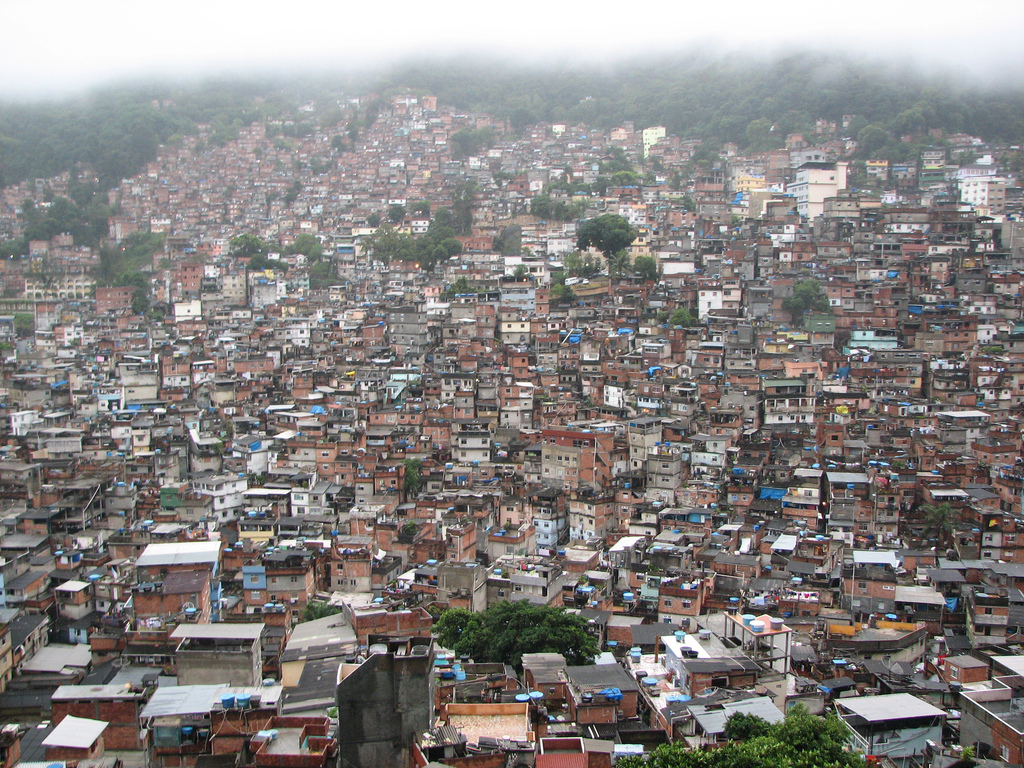

/For those of you who read my last post on The Changebase, you know that I recently signed up to go to Brazil in January. The trip, organized by the Boston University Sch ool of Management, focuses on issues of sustainability, CSR, and social enterprise in the developing country. It sounds like an incredible journey and an amazing way to experience Brazilian life and culture firsthand.

How does that saying go, something about the best laid plans? I’m sad to say that no sooner had I hit the ‘submit’ button on that blog post, announcing my exciting plans for Brazil, the financial realities of this trip set in.

ool of Management, focuses on issues of sustainability, CSR, and social enterprise in the developing country. It sounds like an incredible journey and an amazing way to experience Brazilian life and culture firsthand.

How does that saying go, something about the best laid plans? I’m sad to say that no sooner had I hit the ‘submit’ button on that blog post, announcing my exciting plans for Brazil, the financial realities of this trip set in.

As a former “nonprofiteer” interested in pursuing change through social innovation and CSR, I have never really been focused on making a lot of money. The mission has been what mattered (at least mostly – I mean, let’s be honest: the paycheck was nice!). But now, as an MBA set to graduate in May with a boatload of debt, my financial situation (and more specifically, my earning potential) is certainly top of mind.

I’ve often asked myself: how do I strike a balance between doing good in the world while also making enough money to live comfortably and provide for my family?

The mission-driven side of me says money shouldn’t matter. But the MBA side says, go for the paycheck.

Finding that balance is tricky, and the Brazil trip is just my own most recent example of the tradeoffs that every committed social entrepreneur and changemaker must make in their quest to do good and do well.

While I’m certainly not complaining – after all, figuring out whether I can afford to go to on this trip is what my family calls a “good problem to have” – it got me thinking about all of the talented and motivated people out there whose innovative ideas never got off the ground because of money. How many people with truly world-changing, yet unproven ideas never saw these ideas go anywhere because they lacked the financial resources to make them a reality?

Coincidentally, this week I had a great conversation with someone I met at The Feast who works at Echoing Green. For those of you who don’t know it, Echoing Green is a 22 year-old organization that provides start-up funding – and a support network – to social entrepreneurs in need of resources and guidance.

In essence, Echoing Green is working to ensure that social entrepreneurs with incredible ideas don’t lose out in the battle of trade-offs.

Here's a little bit of background on the social entrepreneurs that Echoing Green is supporting through their innovative funding and support network:

While I’m certainly not putting myself and my money woes on the same level as someone looking to cure disease, bring clean water to villages or improve our educational system, the essential decision-making process seems similar. If money were no object, I’d be on that plane to Brazil in a heartbeat. Unfortunately, money plays heavily in all of my decisions these days – which means this trip isn’t going to happen for me.

As disappointed as I am, this experience has been an important first lesson in what inevitably will be a long string of choosing between tradeoffs.

Is it possible to make money doing what I love? Can I find a job that allows me to make a positive impact, yet one that also provides the financial security I’m looking for? I know I'm not alone in asking these questions, and I guess only time will tell what the answer is.

In the end, I’m left wondering only one thing: Who’s hiring?!

Ok, so we know that local means a lot of things. Does this matter? If we can’t define it, should we really care about eating local?

Ok, so we know that local means a lot of things. Does this matter? If we can’t define it, should we really care about eating local?